Obituary – William Donnegan

By Timothy Fraher

William Donnegan is not a household name today, but in the 19th century he was known as a Black businessman who helped runaways escape from slavery, fought for quality education for Black children and counted Abraham Lincoln among his clients. But it was the violent way in which he died that brought him national attention and played a pivotal role in the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

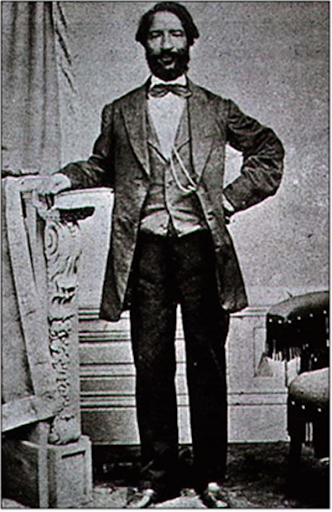

[Left] William K. Donnegan. Source: Illinois Department of Natural Resources [Right] Donnegan’s gravestone at Lot 83, S ½, Block 5 at the Oak Ridge Cemetery near Scott Burton in the “Colored Section” in Springfield. Source: Mike Kienzler, Editor for Illinois State-Journal Register

Donnegan helped to shepherd enslaved people to freedom after he moved to Springfield, Ill. in 1843. He also joined with others in the Black community to preserve the independence of Black schools in Springfield, instead of letting funding and curriculum fall into the hands of the government. The group, known as the Wood River Colored Baptist Association, declared in a letter published in the Daily Illinois State Journal in 1852 that they felt “a deep, very deep interest in our schools, and think it the only sure way to redeem ourselves from the bondage that we are now in.”

Donnegan was also a well-known cobbler, who ran a shop that was frequented by Abraham Lincoln on at least one occasion, according to Richard E. Hart, the author of “Lincoln’s Springfield: The Underground Railroad,” and the owner of several prime real estate properties, according to local newspapers. His success, one newspaper reported, drew the ire of some members of the white community.

“ [He] was a landmark at Springfield and had the respect of everybody and had never been brought to face the law for any reason,” The Freeman, an Illustrated Colored Newspaper reported in 1908. Yet Donnegan was still resented by some in the white community. “First, he was Negro,’’ the newspaper explained. “Second, he owned some of the best real estate in the city.”

“Black success generated social danger,” wrote Roberta Senechal, Professor of History, Emeritus at Washington and Lee University, in her book The Sociogenesis of a Race Riot, Springfield, Illinois in 1908.

There was a third reason why Donnegan’s activities rankled some in the white community. He had been married to a white woman, Sarah Donnegan, for more than three decades. The couple had two children and lived together in a home that they owned, according to the Illinois State Census of 1900.

Victims of Springfield Attacks in the “Badlands”, August 15, 1908. Source: blackpast.org

“[Donnegan] had never been accused of a crime,” Hart wrote. “He had, however, broken the unwritten mores of being married to a white woman.”

When a riot broke out in the summer of 1908, Donnegan became a target.

The violence erupted on the evening of Aug. 14, 1908, when a crowd gathered in front of the Springfield County Jail where two Black men were being detained on suspicion of raping a white woman, according to the Sangamon County Historical Society and the National Park Service, which administers a national monument on the site where the riot took place. As the crowd gathered, the sheriff asked a restaurateur to help move the two accused men from jail in Springfield to the McLean County Jail nearby. The enraged crowd burned down the restaurant owner’s house. Then they began to pillage the rest of the town.

The mob grew to thousands of white residents, according to the National Park Service’s accounting of the riot. Early in the morning, on August 15th, a crowd of rioters found their way to Donnegan’s home, located only a few blocks from Springfield’s Capital Building and Governor Charles Deneen’s mansion. His wife and child managed to flee through the back door, according to a family member. But Donnegan, who was about 80 years old, was overpowered.

The crowd set the house on fire and dragged Donnegan to the street and slit his throat. Then the men dragged him to the schoolyard across the street, tied him up with a clothesline and hung him from a maple tree, according to the report from the National Park Service.

Donnegan died the next morning at St. John’s hospital. After the dust settled in the morning of August 16th, the woman who accused the two imprisoned men of assault admitted that she fabricated the story. More than 2,000 Black people were forced to flee the violence. In the immediate aftermath of the violence, local officials counted nine people dead, according to an article from the New Orleans Times-Democrat published that summer.

Governor Deneen called in the National Guard to quash the riot and as many as 200 were jailed, according to the Santa Fe New Mexican. The grand jury in Springfield indicted ten rioters, three of whom were jailed without bond. One rioter, Kate Howard, drank poison and died after learning about her guilty verdict.

Within a year of Donnegan’s death, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded and its members, including the journalist and anti lynching activist Ida B. Wells. W.E.B. Du Bois described the violent race riot in Springfield, Abraham Lincoln’s hometown, as a catalyst.

In an oral history recorded by the Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum, Charles Wilson, Donnegan’s great-grandson, recalled asking Sarah Donnegan, his great-grandmother, why the mob killed her husband. “Because he was married to me,” Wilson remembers his great-grandmother saying.

“I always wanted to know, ‘where’s Grandpa?” he said. “When is he coming home?’ And she’d tell me that he won’t be home.”

In 2023, Senator Tammy Duckworth introduced the 1908 Springfield Race Riot National Monument Act, which memorialized the Springfield 1908 Race Riot National Monument in Illinois, citing Donnegan specifically.

People in Springfield, such as Doris Bailey, the operations manager at the Illinois State Museum, are determined to educate the next generation of Springfielders about Black residents like Donnegan, who established businesses, engaged in political activism, raised families and educated children.

“I always think of him as definitely a pillar of the community,” Bailey said.